Newspapers from the 1850s and 1860s reveal that Sacramento’s formative years were full of obscure yet dramatic stories. These incidents were big news, even if we’ve never heard of them nowadays. Likewise, many colorful characters have been lost to history, including two key players from the tumultuous years following the upheaval of August 14-15, 1850.

This so-called “Squatters’ Riot” is at least familiar to Sacramento historians – if not the general public. However, it is still one of the city’s least-understood episodes despite having a high death toll that included elected officials: A pair of gun battles killed eight people including the city’s sheriff and assessor, while the mayor was wounded and died later in San Francisco.

This revolt, which erupted at the height of the Gold Rush, is generally portrayed as a single bloody incident. However, the two-day “riot” was only part of a much larger struggle against much worse trouble, and its bloodshed helped trigger the collapse of an economy that was based on land gambles.

Even so, Sacramento’s original industry – speculation, in forms ranging from gold panning to dice – continued, expanding into an impenetrable thicket of contradictory land claims. Land speculators engaged in round after round of wagers throughout the 1850s and 1860s, pitting various titles against various parcels and tracts. This speculation profoundly undermined local property rights – and values. The city became a great betting table on which titles changed hands like poker chips.

Ownership of Sacramento’s land became increasingly unclear. The resulting chaos was so severe that it effectively overruled the United States Supreme Court, whose 1864 U.S. v Sutter ruling seems to have had no lasting effect beyond casting a legal aura on Sacramento’s ongoing mayhem.

How is it possible that such turmoil is now unknown to most Sacramentans? The answer may lie in a legal free-for-all that exploded during the spring of 1868 – at which point things got so bad that the community may have been willing to simply forget the truth and move on.

Lurking behind this latter event – infamous in those days as “the ejectment suits” – are two unknown characters who inflicted particular damage on the city’s unstable real estate scheme. When one considers how this duo’s ruthless greed prolonged and worsened the land crisis, it is hard to believe that Sacramentans are not familiar with the names of Sanders and Muldrow.

A City Built on Mud

Sacramento’s system of land ownership rests on a foundation as soft and squishy as the physical bottomlands on which the city sits. The legal mess began with Sam Brannan’s crooked land scheme, which laid out Sacramento’s grid. This scheme divided up land falsely claimed by Johann Augustus Sutter, who supposedly lost his paperwork for a 76-square mile grant actually located near Marysville. Sutter’s Fort was actually a huge squat on public land, and it provoked a failed local revolution, later misnamed as a mere riot.

The trouble didn’t end with the suppression of this organized (and eventually armed) uprising. It wasn’t even resolved by the United States Supreme Court, which eventually declared Sacramento to be Sutter’s, despite clear and overwhelming evidence to the contrary as well as serious problems with the supporting evidence.

In any case, the court’s ruling utterly failed to resolve the matter. Sacramento’s land trouble stretched at least until 1868, when an astonishing wave of litigation overwhelmed the courts here. In the second half of April, roughly 700 “ejectment suits” were filed against thousands of residents, brought by about 140 purported Sacramento landowners (and parties). For perspective, the city had a total population of only about 16,000 souls at that time. Most of Sacramento was dragged into court.

Although not everyone with means participated in the grand gambles that upended Sacramento, it appears that bets were placed by people from across the social spectrum. The bettors included both scoundrels unknown to history and famous men who abused their power to build on already substantial wealth. (More on that in my next post!)

The troubles of 1868 were inaugurated by William Muldrow, whose wager involved unpaid loans to Sutter – bad debt that he had purchased. Muldrow is almost entirely absent from the historic record, despite his causing a lot of trouble for this town as he wrangled with Sutter’s trustee, Lewis Sanders, Jr.

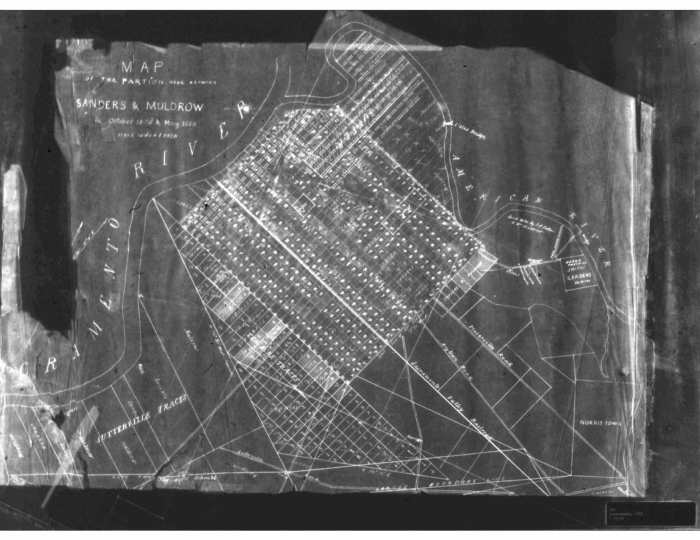

Sanders and Muldrow appear to have divided up the town with some sort of gentleman’s agreement. A map kept at the California State Library recalls an event that seems to have been otherwise unrecorded: “the partition made between Sanders and Muldrow” between 1858 and 1860.

This map is of unknown provenance, but someone thought it was historic enough to enter the state’s collection. This tattered document is a rare relic of an important story that was almost successfully hidden from history. It is one of very few surviving artifacts from Sacramento’s darkest times.

Although the map’s partition makes no sense at first glance, the city was divided in ways that resonate with the pair’s roles in other events that unfolded around that time: the ejectment suits of 1868, as well as an earlier high-stakes bet.

Sanders’ Gamble

In 1857, Sanders shocked Sacramento by announcing an auction of large portions of the city’s land, including 400-yard sections of waterfront. His announcement in the Sacramento Union described this as being “for the purpose of satisfying and paying out of the proceeds of that portion held in trust, certain debts of Wm. Muldrow and others.” (1/21/1857)

Despite the absurdity of Sanders’ attempt to sell the land out from under the city, Sacramento stopped in its tracks. The Union reported, “The proceedings of Col. Sanders, as the Trustee for Gen. Sutter, are developing a strange condition of things in this city, as well as producing no small degree of excitement and indignation.” (2/7/1857)

The City itself filed suit to stop the sales, while the Union frantically churned out documentation and analysis of what was clearly the biggest news story of the winter. The auction was eventually postponed after several tumultuous weeks, because “the parties have not yet ascertained what lots they are, in their own estimation, entitled to sell.” (2/17/1857)

It seems that Sanders’ the auction was not held. His wild bet did not pay off. But he laid the groundwork for another decade of trouble.

Muldrow’s Suits

As severe as the impact of Sanders’ mischief may have been, Muldrow eventually outdid his old rival. One day, in April of 1868, he marched into the clerk’s office and filed 17 lawsuits.

These were no ordinary lawsuits. Muldrow reportedly caught 3,000 neighbors in his mind-boggling web of defendants.

Consider case #11994, which is the only file I’ve found at the Center for Sacramento History: Muldrow sued a couple dozen named individuals and estates, a John Doe, the City of Sacramento, and “all possessors of the hereinafter named property.” It then describes the land – streets and alleys included – bounded by Front, V, X and 31st Streets.

He claimed 60 entire city blocks. Not parcels. Blocks.

As mind-boggling as it might seem to launch a single lawsuit against everyone living on five dozen city blocks, this was typical for Muldrow. Several of his other suits each ensnared everyone living within other strips of the city, stretching from the waterfront to what is now Alhambra Boulevard – the land north of C, along with that between D and F, I and L (90 blocks!), P and R as well as S and U were also listed.

In all, Muldrow sued the residents of more than half of Sacramento’s entire central grid – 390 blocks! And this is not even counting his claim on the waterfront and public squares, as well as a vast number of parcels surrounding the city.

These huge swaths correspond to the markings on the partition map: With few exceptions, Muldrow sued for the strips of central city land that were not marked for Sanders’ in their partition map.

Clerk’s Office “Rendered Lively”

One would hope that the community could simply disregard this duo’s ongoing legal shenanigans. But alas! It was not to be.

After Muldrow’s trip to the clerk’s office, hundreds of people started filing their own suits. The Sacramento Union tried frantically to keep track of a legal battle royale as it unfolded: On the second day of the crisis, it reported that, “The office of the County Clerk was rendered lively yesterday by the filing of an indefinite number of ejectment suits. Everybody seems inclined to bring suit against everybody else, for the recovery of whatever real estate they may happen to possess.” (4/16/1868)

Another day’s column concluded another long list of suits, along with a disclaimer: This report was “but a small proportion of the suits commenced yesterday, and it was expected that by midnight last night about two hundred more complaints would be filed.” (4/18/1868)

For several days, lines of would-be plantiffs stretched out the door, in a manner that the Union compared to election day. Then the paper appeared to give up on listing suits.

Then, the true severity of the situation was revealed by the Union’s May 2 edition, which devoted its front and back page to describing the suits in miniscule type. This was nearly a quarter of a daily paper’s print space, on pages usually devoted to ads!

This apparently unique act of journalism suggests that it must have been an incredibly tense time. Remember, this was all four years after the U.S. Supreme Court supposedly settled the bloody matter of Sutter’s land grants, which Sanders had stirred up in 1857. Muldrow was ripping open that can of worms, all over again.

Who Were These Guys?

The events of 1857 and 1868 paint a picture of a legal environment that was impervious even to the decree of the United States Supreme Court. It seems that two private citizens were able to destabilize the city with only moderate effort.

So who were Lewis Sanders, Jr. and William Muldrow?

I have not yet tracked down details, but we can find clues about the nature of these villains in another filer of suits, who is somewhat less obscure: General Lucius Harwood Foote.

Foote had an illustrious legal and diplomatic career. But there is a gap in his biographies. This interruption included 1868, at which point it turns out that he was a police court judge here in Sacramento. He seems to have severely abused his power by exploiting the city’s land title confusion.

Foote’s actions inspired ejectment suit defendants to call for his resignation – singling him out for condemnation from the rogues’ gallery that was besieging the city. His role in the crisis will be addressed in part two of this post. Coming soon…

[…] More to come… […]

LikeLike

[…] This battle royale overwhelmed the city’s legal system in the weeks following William Muldrow’s shocking attack on Sacramento’s property holders (which I described in the previous post). […]

LikeLike

[…] Sacramento’s early years. The speculators apparently lost this battle, but as shown by the later antics of Lewis Sanders and William Muldrow – to say nothing of the community’s panicked response to said antics – the war was far from […]

LikeLike

Lewis Sanders, Jr. was born in Kentucky, where he practiced law. He relocated to Natchez, MS, where he continued practicing law. His Natchez law partner was James Ben Ali Haggin, who married the daughter of Lewis Sanders, Jr. Haggin relocated–first to New Orleans and then to Sacramento. Lewis Sanders followed the Haggins to Sacramento, where another of his daughters married Lloyd Tevis. Haggin and Tevis became business partners–they are both easily found in a google search. I think Lewis Sanders died about 1865 in California..

LikeLike